Commentary by:

Dr. Arun Ghoshal, Clinical Fellow in Palliative Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Center, Toronto, CA

Feature Article:

Battista, V., Baker, D. J., Trimarchi, T., Sabri, B., D’Aoust, R. F., & Wright, R. (2021). Advance Directives for Adolescents and Young Adults Living With Neuromuscular Disease: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing : JHPN : The Official Journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association., 26.

View the Issue #10 Citation List in the Library

View a PDF of the Issue #10 Citation List

The world is now home to the largest cohort of adolescents in history – 1.2 billion people between the ages of 10 and 19. Both between and within countries there is much variation in the definitions used to describe the Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) cancer population. In the United States, the 2006 Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program report used the 15–29 age range,1 while the 2006 Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group (AYAO PRG) report used 15–392—now the standard used by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as well as the age range generally used by JAYAO. Canada generally uses the same 15–29 age range as SEER,3 while Australia tends to favor 15–25.4 In the United Kingdom, the Teenage Cancer Trust focuses on teenagers and young adults (TYAs) aged 13–24,5 though European members of EUROCARE employ the 15–24 bracket.6

Editor’s recommendation for the age range defining the AYA oncology population is to subdivide NCI’s 15–39 age range into three age cohorts: early young adulthood (15–18 years old), young adulthood (19–24), and late young adulthood (25–39); to best account for the differential physiological and psychosocial realities experienced by AYAs within each age category.7 AYA comprise a distinctive demographic whose priorities of care are not always congruent with those for older adults.8 The issues faced by AYA patients are complex, with psychosocial, interpersonal, and developmental challenges not typically encountered by other patient populations, particularly during transition from pediatric to adult services,9 or with the involvement of parents/guardians in the care though many AYAs are adults in the eyes of the law.10 This article was chosen to highlight this important but often neglected aspect of consultations in AYAs.

Out of 307 studies retrieved from database search, only 5 (1.6%) were included for this review, which reflects the paucity of literature in this aspect. Four themes emerged from the literature:

- conversations about advance directives with adolescents/young adults with neuromuscular disease are not being conducted

- only a small number of patients have documented advance directives

- patients want to have conversations about goals of care and want to have them sooner

- there is a lack of evidence in this area.

These findings will influence neuromuscular clinicians’ practice surrounding the use of advance directives and increase their knowledge regarding the need for discussions regarding goals of care, and some preliminary work has been done in that regard as well.12

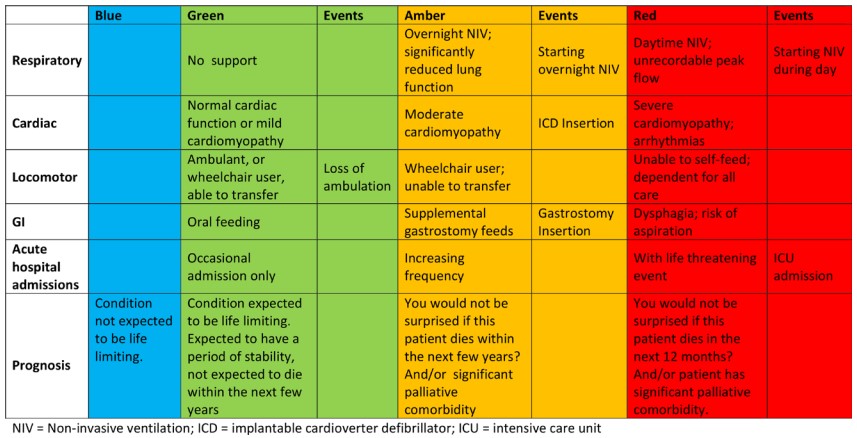

Using the ‘The Spectrum of Children’s Palliative Care Needs’ classification to identify when to introduce advance care planning, a traffic light system has been developed specifically for neuromuscular patients. This categorises patients as ‘red’, ‘amber’, ‘green’ or ‘blue’ based on cardiac, gastrointestinal, locomotor and respiratory status, recent hospital admissions and prognosis. As with The Spectrum of Children’s Palliative Care Needs, the over-riding factor is that of prognosis. This asks clinicians if they would not be surprised if the patient were to die within 12 months (red category) or a few years (amber). This is a commonly used concept in palliative care and distinct from expecting the patient to die within that time frame. The system also includes events that could lead to a change in category, which may prompt advance care plan discussions.12

Figure: Neuromuscular Traffic Light Tool. NIV, non-invasive ventilation; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; ICU, intensive care unit; GI, gastrointestinal. Adapted from Willis et al. (2021).12

- Bleyer, A., O’Leary, M., Barr, R., Ries, L.A.G. (Eds). (2006). Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975-2000. National Cancer Institute, NIH Pub. No. 06-5767. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/publications/aya/aya_mono_complete.pdf

- Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. (2006). Closing the gap: research and cancer care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer. NIH Pub. No. 06-6067. https://www.livestrong.org/sites/default/files/what-we-do/reports/ayao_prg_report_2006_final.pdf

- Canadian Cancer Society. (2009). Canadian cancer statistics 2009.

- CanTeen, Cancer Australia. (2008). National service delivery framework for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Australian Government. https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/national_service_delivery_framework_for_adolescents_and_young_adults_with_cancer_teen_52f301c25de9b.pdf

- Teenage Cancer Trust. (n.d.) https://www.teenagecancertrust.org/

- Gatta, G., Zigon, G., Capocaccia, R., Coebergh, J. W., Desandes, E., Kaatsch, P., Pastore, G., Peris-Bonet, R., Stiller, C. A., & EUROCARE Working Group (2009). Survival of European children and young adults with cancer diagnosed 1995-2002. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990), 45(6), 992–1005.

- What Should the Age Range Be for AYA Oncology?. (2011). Journal of adolescent and young adult oncology, 1(1), 3–10.

- Kenten, C., Ngwenya, N., Gibson, F., Flatley, M., Jones, L., Pearce, S., Wong, G., Black, K. M., Haig, S., Hough, R., Hurlow, A., Stirling, L. C., Taylor, R. M., Tookman, A., & Whelan, J. (2019). Understanding care when cure is not likely for young adults who face cancer: a realist analysis of data from patients, families and healthcare professionals. BMJ open, 9(1), e024397.

- Wein, S., Pery, S., & Zer, A. (2010). Role of palliative care in adolescent and young adult oncology. Journal of clinical oncology, 28(32), 4819–4824.

- Grinyer A. (2009). Contrasting parental perspectives with those of teenagers and young adults with cancer: comparing the findings from two qualitative studies. European journal of oncology nursing, 13(3), 200–206.

- Abdelaal, M., Mosher, P. J., Gupta, A., Hannon, B., Cameron, C., Berman, M., Moineddin, R., Avery, J., Mitchell, L., Li, M., Zimmermann, C., & Al-Awamer, A. (2021). Supporting the Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults: Integrated Palliative Care and Psychiatry Clinic for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Cancers, 13(4), 770.

- Willis, T. A., Macfarlane, M., Vithlani, R., Bassie, C., Kulshrestha, R., & Willis, D. (2021). Neuromuscular diseases and advance care plans: traffic light system. BMJ supportive & palliative care, 11(1), 116.